Enhancements

There seem to be a lot of articles around right now about book-apps. Are they the future? Or are they hurting our ability to imagine? Are they more immersive? Or are they an interesting sideline but no mainstream? Reading these articles, and their comments, reveals a definite schism in viewpoint, between those who are excited - perhaps too excited - by a digital future of video and audio-rich content; and those for whom reading is a precious, fragile thing that we cannot afford to lose.

The Future is Here Already

An argument often touted by the pro-camp is that the internet, and multi-media content in general, is all about reading. People are reading, if such a thing can be measured, more than they ever have before: only they're reading differently - in snippets and bursts, skidding from point to point, article to article.

Of course, the same example is used by the negative camp, as a reflection of our diminished attention spans, our inability to read long books. So where's the truth?

And while there seems to be popular acceptance for enhanced textbooks and children's book apps, what about narrative fiction? Perfect form, or sacred cow?

The discussion often raises the spectre of CD-ROMs: produced to great hype in the Nineties and destined to produce a digital future which never took off. The CD-ROM, one commenter tells us, has been reduced to a footnote. That seems a little unjust, however: the structure of the modern Web is based directly on the model laid out by the authors of CD-ROMs. What those products lacked, and what gave Wikipedia the killer edge over Encarta, was the network effect. CD-ROMs didn't fail because they were too digital: rather, they weren't digital enough.

Digital Narratives

Narrative is different, of course. Narrative is linear, "hard-coded"; there's no obvious benefit to networking a narrative, and there are some obvious costs. A reader of a novel has a single point of focus - the written line of text. Adding a video causes a conflict. Where should the reader look? Do we want them to lift their eyes off the page as they try to decide? And adding background effects - spot sounds, for example, screams and clattering carriage wheels - surely that detracts from the imaginative world of the book?And what about messing with linearity itself? Can narratives survive being scattered and reformed in whatever order a reader might decide?

What works?

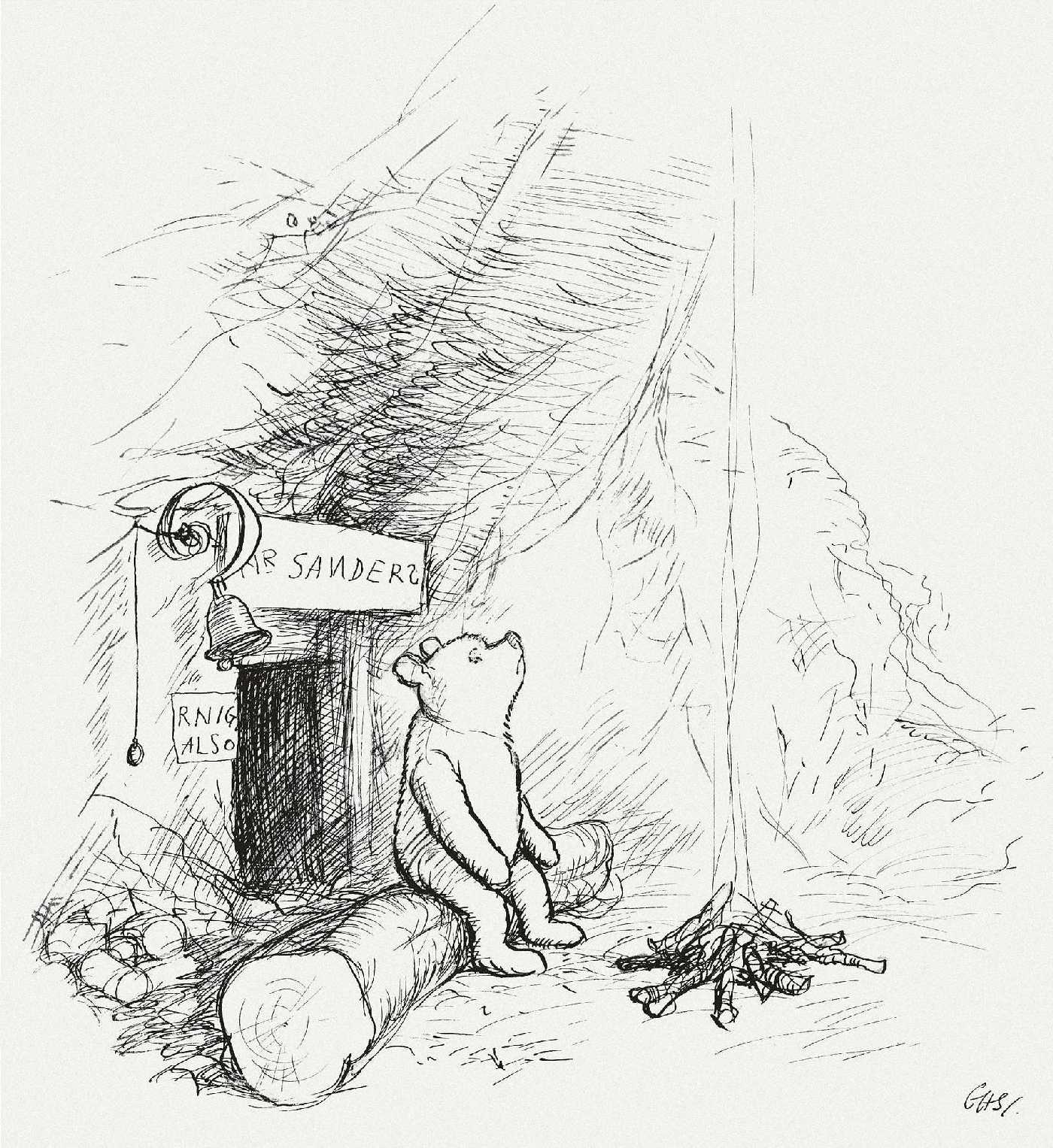

There's no blanket answer to these questions. It's pretty clear they cover a wide spectrum. Are spot sound-effects really different than spot-illustrations? Do they affect the reading process any differently than, say, than E. H. Shepard's wonderful drawings for Winnie The Pooh? What if our sound designer is talented, soulful, with a good understanding of the text? Do we need sound-effects in text? Probably not. Do we need illustrations? No. Do they add value to the experience? They can do, yes. Do they make it more immersive? Hard to say. Tell you what, let's just say good when we like what we see, and bad when we don't, perhaps?

Enhancements can be badly done. Really badly done. They can be distracting, confusing, messy; they can be pointless, soulless. A lot of what's been done with enhancing digital books has failed because, it seems, no-one thought to carefully about how the reader was going to feel about it all. In fact, working out how enhance a book well is probably a much harder problem than the technical business of doing it. But do it well -- and maybe you get The Waste Land.

Focus!

The issue of focus is, to my mind, a more serious one. Including a video does distract from text - and while it may well be appropriate in non-fiction, it's hard to imagine a world in which video embedded alongside text isn't a gimmick. But that said, video as a transition between sections of text, like the cutaways of locations used in film and TV to introduce a change of location, could easily become as frequent, as normal, as a atmospheric quote at the start of a chapter. Again, do we need this? No. Could it add value? I don't see why not.What about non-linearity? This is thorny. After all, reading is inherently linear - and when it isn't, like on the Web, it can be unsatisfying, hard to sustain, idle. If you're reading this blog, you probably know that with Frankenstein, we've introduced interactivity into the heart of our text. I can see that raising eyebrows on both sides of the enhancement divide. After all, now you can't read the novel as a novel, even if you mute the audio and ignore any widgets that might come your way. That sounds bad.

Except, this isn't a novel. It's an inklebook.

Frankenstein

In Frankenstein, the reader is in conversation with the protagonist. Not occasionally - all the time. That's how the book is read. Where on a Kindle you'd press the "next page" button, here you offer Frankenstein a piece of advice, or ask him a question. It's not an enhancement, it's a different medium. You might hate it - that's your call! - but I don't think you can argue "it's a book done badly" or it's an unnecessary enhancement. Without the functional part there is no story, no book, and Dave Morris can't tell his tale.

In Frankenstein, the reader is in conversation with the protagonist. Not occasionally - all the time. That's how the book is read. Where on a Kindle you'd press the "next page" button, here you offer Frankenstein a piece of advice, or ask him a question. It's not an enhancement, it's a different medium. You might hate it - that's your call! - but I don't think you can argue "it's a book done badly" or it's an unnecessary enhancement. Without the functional part there is no story, no book, and Dave Morris can't tell his tale.

In short, Frankenstein is not an enhanced book. But it is a book.

With the interactivity - with the flow, the conversation between reader and narrator, the give and take of reading and speaking - the story unravels beneath your fingertips. It's part-novel, part improvisational theatre.

But, at the same time as being a new way of reading, Frankenstein is also not about the technology. If we've done our job well - and I hope we have - then you won't notice that there's an app there at all. You won't be distracted because you'll just be reading a story. One that we hope is immersive, by which I mean, good.

And it's got some illustrations. We like them, they add to the mood. Call them enhancements, but only if you must.