Hello! We're inkle - we made 80 Days, Heaven's Vault and Overboard!. Now we're making A Highland Song. Follow along with our progress right here!

Autocut!

—Here at inkle we're currently into the closing stages of work on our upcoming Scottish adventure, A Highland Song. It's a 2D platformer with climbing, running and jumping - and narrative elements. As the protagonist, Moira, explores the hills and caves on her way to sea she'll find things to investigate and characters to talk to.

So far so good - but there's a problem with mixing adventure gaming and platforming. In adventure games, it's usual for the player to walk up to an interactive object and stand in front of it while the protagonist describes it. But platformers are all about motion. Taking away control from the player feels bad.

So how do we keep things feeling snappy and responsive, while still allowing the player to get stuck into a good inkle-style conversation if they want to?

Put another way, how do we let the player get knots-deep into a conversation - while still being able to walk away at any moment?

Autocuts

Enter the "autocut": two variables we set at the start of a conversation or interaction which are observed on the game side.

~ autoCutZone = WOODSMAN_TRIGGER_VOLUME

~ autoCutKnot = -> leave_woodsman

For those who know ink, the first of these variables takes a LIST value, which specifies a volume in the world. Should the player, who's still free to move, step outside of this volume, the game uses ChoosePathString to divert immediately to the knot specified in the second variable (and it wipes the autocut values to prevent an infinite loop).

So perhaps you meet a friend who wants to stop and chat, but the sun is going down and you need to get away... you can. And if you meet a lonely poet and ask him for a sample, and he starts to recite at length... you don't have to wait for him to finish before you vote with your feet.

And for almost every conversation in the game, we don't block the player's control at all.

(And should the player - or the other character - finish the conversation with a friendly farewell instead, we simply empty the autoCutZone variable and move on as normal.)

Simple but powerful

It's a simple system, but we're finding it incredibly effective: a game-character can be mid-exposition and the player can simply walk off... and the character will react. They can bid you farewell, remark on your rudeness, or even shout something to try and lure you back.

We can even define a second, larger trigger volume to give the player another chance to really walk away... and so forth.

And ink can still track which bits of content you've seen and which bits you've skipped. So despite having a trapdoor anywhere in any conversation, it doesn't make the flow more complex or damage the script's continuity. We can still test the flow in inky or with an automated tester.

Keeping things moving!

So while the character might still pause on the spot if they're reading a signpost or picking something up, they'll never get stuck in a conversation they don't want to.

... Although, of course, turning your back on someone can have its consequences too...

Letters

—A Highland Song is described in the blurb of our announcement trailer as "a narrative adventure with rhythm and survival elements". It's also a game about walking across the wild and empty Scottish highlands, alone.

So how does one tell a story, when you're on your own?

A lonely trek?

Games are a bit peculiar when it comes to telling stories with only one character: in films it's usually considered a basic requirement to have two people going on a journey together (so they can argue along the way), and even the most introspective books usually move their protagonist from human encounter to human encounter.

But games with solo protagonists going on lonely journeys are common, whether it's Breath of the Wild or Elden Ring. As players, we're used to long stretches without storytelling (or with purely "environmental storytelling", which is really another word for "set dressing") as we go from village to town, or from NPC to NPC (or to a coffin on the edge of a lava waterfall, for some reason).

inkle's games are usually different. When you travel the world in 80 Days you're in constant contact with your master, Phileas Fogg; and when you sail the rivers of the Nebula, your robot Six is heckling you the whole time. But then again, for most of Sorcery! you're a lone adventurer (unless you've been cursed by a talkative, grumpy wizard, I suppose.)

What's made A Highland Song more difficult, though, are the Highlands themselves. There are no villages or towns between Moira and the sea. There are some characters, but not too many - too many, and these empty wilds would start to feel weirdly crowded. Not only that, but the journey goes ever-forwards, so players can't backtrack from one character to another: the people you do meet are quickly left behind.

There are no shops to buy upgrades from, and no bandits or tricksters on the roads. So where and how does a narrative arise?

Walking and thinking

We realised early on in the project this was a game about walking. And when one's out walking, after a while, things arise - thoughts, feelings, memories... Walking is a way of shaking out your brain and seeing what sticky things come loose. So as Moira walks she has ideas, and thoughts - and she remembers things, the most common of which are things written to her by her Uncle Hamish, who has been sending her letters since she was small.

As the narrative designer on the project, one of my jobs is to ensure that what Hamish has to say is - to be blunt - interesting. I might write a wonderful series of remarks on the subject of wild Scottish heather, but if the player hasn't seen any, doesn't know what it is, and anyway, is up in the snow-capped mountains at this point where the heather doesn't grow, it's not going to be very relevant.

This is always a tricky problem in games (how often has a game character shouted out a useful hint or piece of advice to you in a game? And how often was that advice actually relevant a moment earlier, but not any more?) But in a game about stories, and legends - and in a game with a mystery at its heart, which A Highland Song has - it's not just about making sure the storytelling is relevant. It wants to be more than relevant. It wants to be rewarding.

Letters, and letters back

It was on a walk (from a coffeeshop to home) when I understood that I'd been missing something. The problem with Hamish writing you letters (well, having written you letters that you're now thinking back on) is that, unlike a conversation with a sidekick, you don't get to ask questions in return. You can't lead the conversation; you can't focus on what you're interested in; you can't follow up...

... but the other thing about Hamish having written you letters, in the past, is that Moira might well have written letters back. Letters in response to Hamish's letters: letters asking him questions, or asking for more information.

Of course, all those letters were written well before the game started... but what did Moira ask? What should she have asked? Those are exactly the kinds of decisions we like letting the player take for the protagonist.

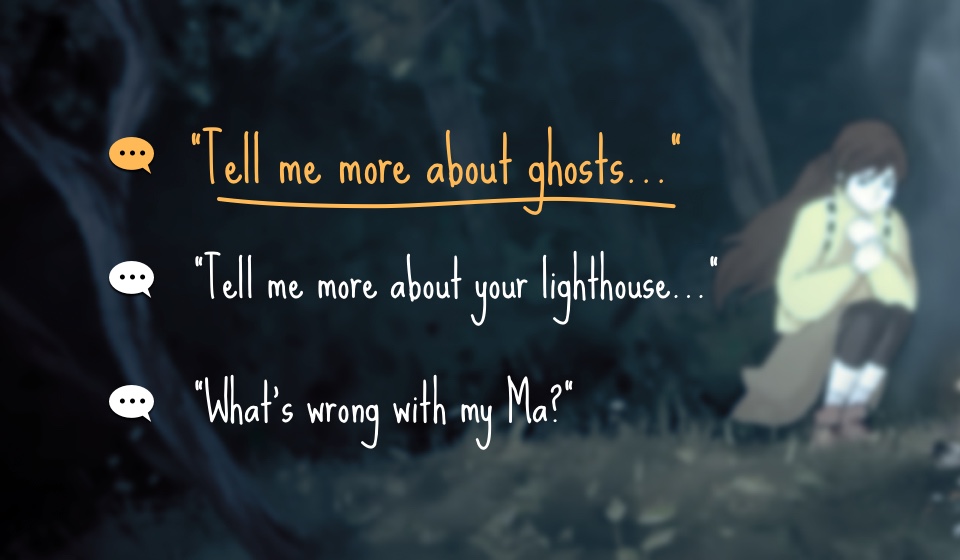

Conversation by correspondence

So that leads us to Highland's core "conversation" mechanic, which is perhaps the oddest one we've ever built. As you settle down to sleep, Moira will recall a letter she wrote to her Uncle, asking him something... and she'll recall her Uncle's reply; a little fragment of story, legend, memory (or, like, a joke), all of which add up to form the main narrative thread that winds from peak to peak as you make your way to the sea.

And like the conversations that pass between Aliya and Six in Heaven's Vault, what Moira can ask about is highly contextual, driven by what you've found and what you've seen, by what you've learned recently... What Moira remembers is decided by whatever's at the forefront of Moira's mind, and what threads she's been following.

Guide her to ask more about the ruined castle known as the Outer Wall, and you might learn more about the legendary Queen Morag, which in turn might bring up further questions... but change the subject to Uncle H and his lighthouse, and you'll learn something else.

Explore without and within

A Highland Song is always going to be a game about being on your own, in a place much bigger than you, for which you're ill-prepared. But even if you're alone, you don't need to be lonely. We all carry a universe of voices inside our heads, and there's plenty to explore inside as well as out.

I said above there's a mystery at the heart of the game. Rest assured: Moira has all the answers she needs; if she can only find them...

Animation and Climbing (video)

—Learn all about our progress on animations and our climbing mechanic in our latest update, this time in video form!

Rim-lighting test

—We're a small team, so it's critical that we find ways to be efficient with every part of production.

We love to find simple yet powerful building blocks that can be reused in different ways. Here's a great concept that Paul came up with - a straightforward way of adding rim-lighting to all our objects in the world.

On top of our base cloud texture there's an additional lit layer. By masking this off based on a blurry light source texture, we can get a lovely effect as the light passes over it. This can potentially be used for everything in the game - the mountains themselves, the clouds as shown below, as well as trees, buildings, and perhaps even characters.

Welcome to Flora, animator extraordinaire!

—A few weeks ago we put out a call for animators. Well, that call was answered by lots of incredibly talented individuals, and we're delighted to say we're now working with the brilliant Flora Caulton (check out her amazing portfolio!)

Here are some initial animation sketches for our protagonist. We're super excited to see these hand-drawn animations going into the game!

The Songlines, by Bruce Chatwin

—Joe had the idea for our highland game.

The "idea" here doesn't mean the idea of setting a game in the Highlands (okay, he had that idea too), but rather the "idea" is the "idea" which sits at the heart of the game and makes the game into this game. It's the idea we haven't talked about yet (except occasionally, by accident.) We've not formally declared: "hey, we had this idea."

We didn't. Joe did. And it's a great idea.

But when he told me the idea - which I'm not about to tell you, now - it reminded me of something. And for a long time I couldn't put my finger on it. When I say a long time, I mean multiple years, because Joe told me this idea in 2017 and I just realised what it made me think of.

If you want to know, the clue is in the title of this post. It's a book called The Songlines by a writer called Bruce Chatwin.

The Story of a Journey

The Songlines was published in 1987, which makes it essentially ancient history at this point. I read it much later, after writing a play about two explorers in a post-apocalyptic desert arguing about whether a line of burnt-out cars indicated a path to follow or not, when various people in my family told me my play was "basically just The Songlines". They were wrong - my play had more jokes in it, and ends on a gunshot - but they were also right; the play, like the book, was about route-finding, about journeys, stories and lines.

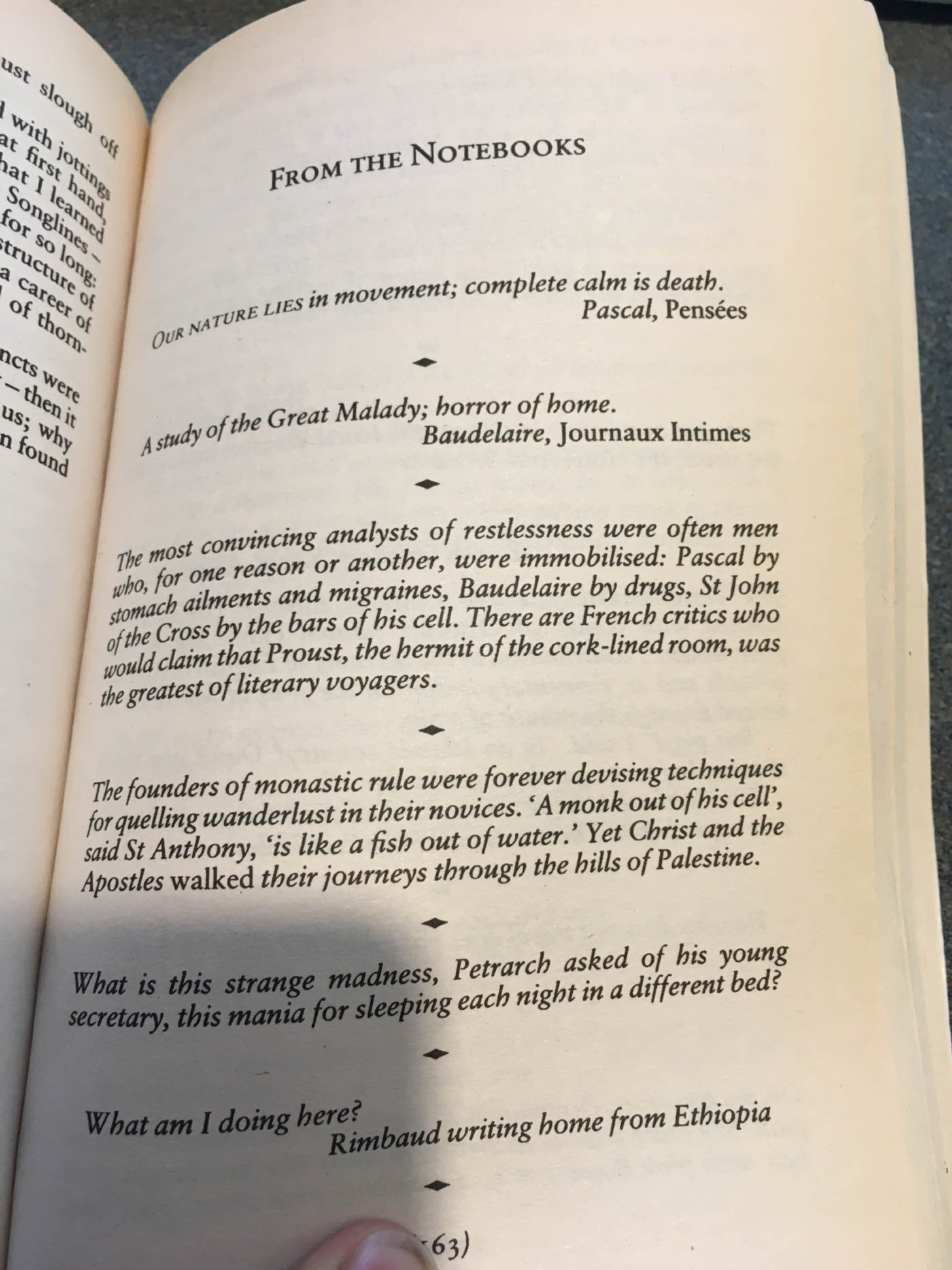

It's a sort-of anthropological book; it describes a journey by the author into Australia. I can't remember what happens on this journey and it's not terribly important. But the book culimates in a collection of thoughts about walking: what it means to walk and how people know which way to walk.

It proposes that us humans are not defined by being "the animal that talks".

We are "the animal that walks".

That sounds ridiculous but it isn't, it's really fascinating.

(This, by the way, is what I think anthropology is supposed to do: take something really mundane and then make you realise how fascinating and bizarre it is. My favourite example of that is "the three-second rule"; the one that allows you to eat crisps which have fallen on the floor of a pub, but only if they've been there for three seconds or less. After that, they become instantly disgusting and filthly. That's sensible, right? Wait. No, it's not. Anyway.)

The Journey of a Story

One of the things discussed in The Songlines (which, I should warn you, may or may not be true, and may be massively oversimplified) is the way Aborigines use stories - songs - as a way to navigate the enormous terrain of the Australian interior. Without maps (there being no paper, presuambly), the traveller recalls a tale, the major beats of which take place at major landmarks along the route. Here is the tree where the story begins; here is the rock where it continues; here is the river the characters crossed; and here is the ending, right where we wanted to go. The stories are the journey, and the journey repeats and reinforces the story.

The sounds ridiculous, doesn't it? Except, only, how many times have you walked through a city and said to your friend, "we go past the place where we met so-and-so; then turn left at that tree you tried to climb but feel out of; then right at the cinema complex where you were stood up that time; and then it's at the end of the street."

The Joy of Walking

This game is a journey about stories, that form the story of a journey. It's also about how glorious, how basic, how simple and how delightful it is to walk.

And when walking is truly delightful, one breaks into...

... ah, now, but that would telling.

The Call of the Wild!

—

Every narrative project has to start somewhere - with something you're trying to hit. The highland game's different than most of our previous games because we're trying to hit a feeling. (You'll know it when you see it, I think.) So the narrative part of the game has a different job than it might sometimes: get out of the way quickly, then hold the game up high.

This is a game about going out into the wilds, and not knowing if you're coming back. Which sounds super dark and scary: but this isn't a scary game. You aren't going to get eaten by wolves. (You're more likely to turn into one yourself, perhaps. We'll see.)

So - who are you, and why are you doing it?

We tried some ideas that were adventure stories. After Hitchcock and the 39 Steps, you're a spy, crossing the hills to avoid escape. (Joe pointed out it could almost be called "Over the Highlands" at that point. It's a fair cop.)

Something more grounded then. You're a teenager and you're running away from home. That's almost this game. But if you're running away from something it's not quite the same as running towards something, is it? With every step away from something the tension recedes and only regret or "oh God it's chasing me" can step in. With running towards something, you can anticipate. You can wonder what you'll find. And - in classic inkle style - you can worry about being late.

So what's across the Highlands that's worth running towards? And who runs? And while you're running, what do you find?

I've done a lot of hill-walking - not in Scotland, as it happens, but in the Borders. For me, the thing I always loved is seeing a peak and striking out for it, getting there somehow or other. The stories of a place are there to help you arrive, and help you set out for the next hill.

What's in the Highlands waiting to be found? And will it pull you off your journey, or push you further along?

Ah, now that sounds like the makings of a tale.

Trees and stone skimming

—Here's a quick snapshot of what some of the team has been up to this week!

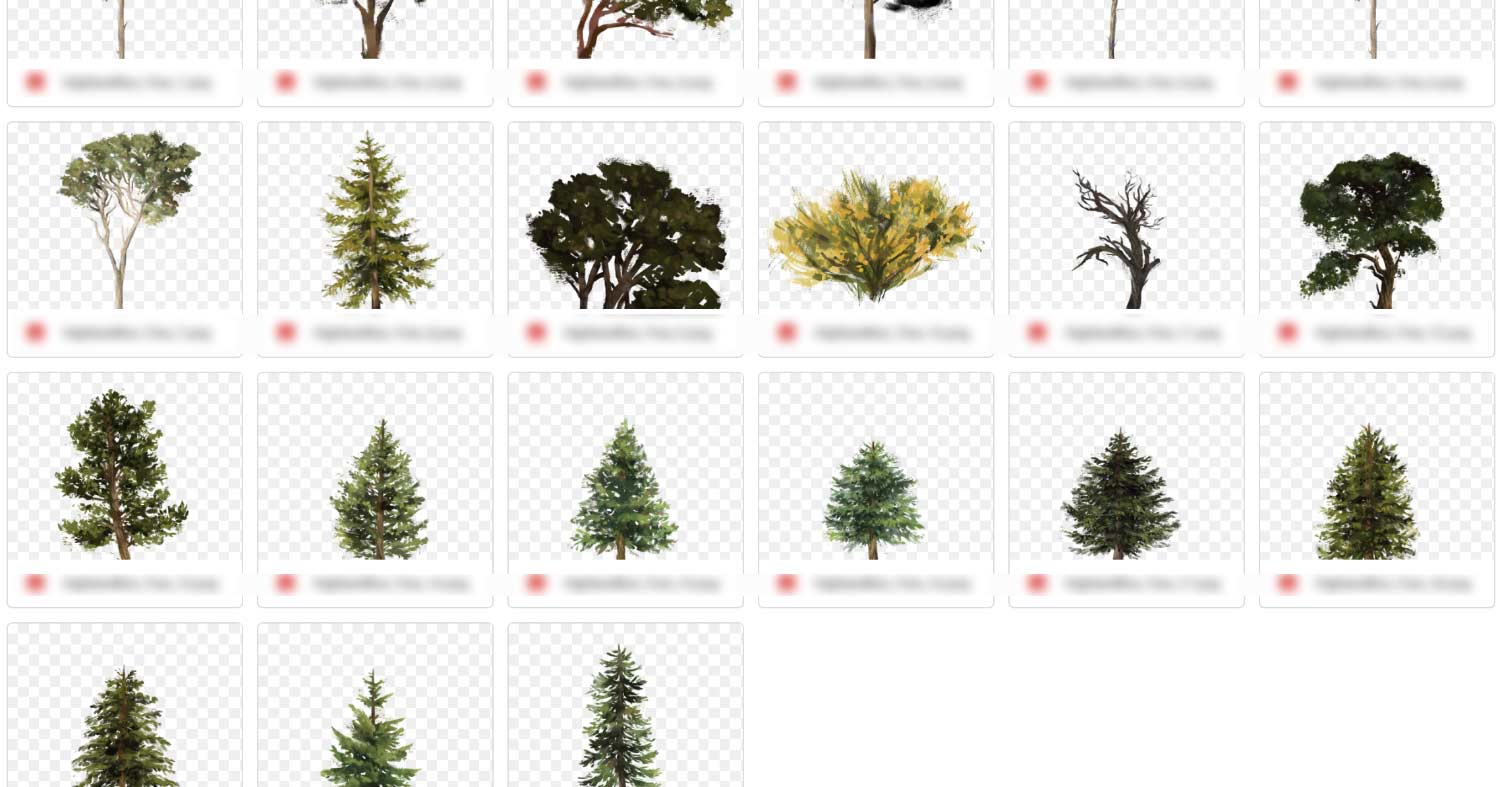

Annie has been starting to paint lots of scenery! We're going to need loads of rocks and trees in the game to make it feel lush, with lots of unique features, hopefully without too much repetition! Here's a few of them:

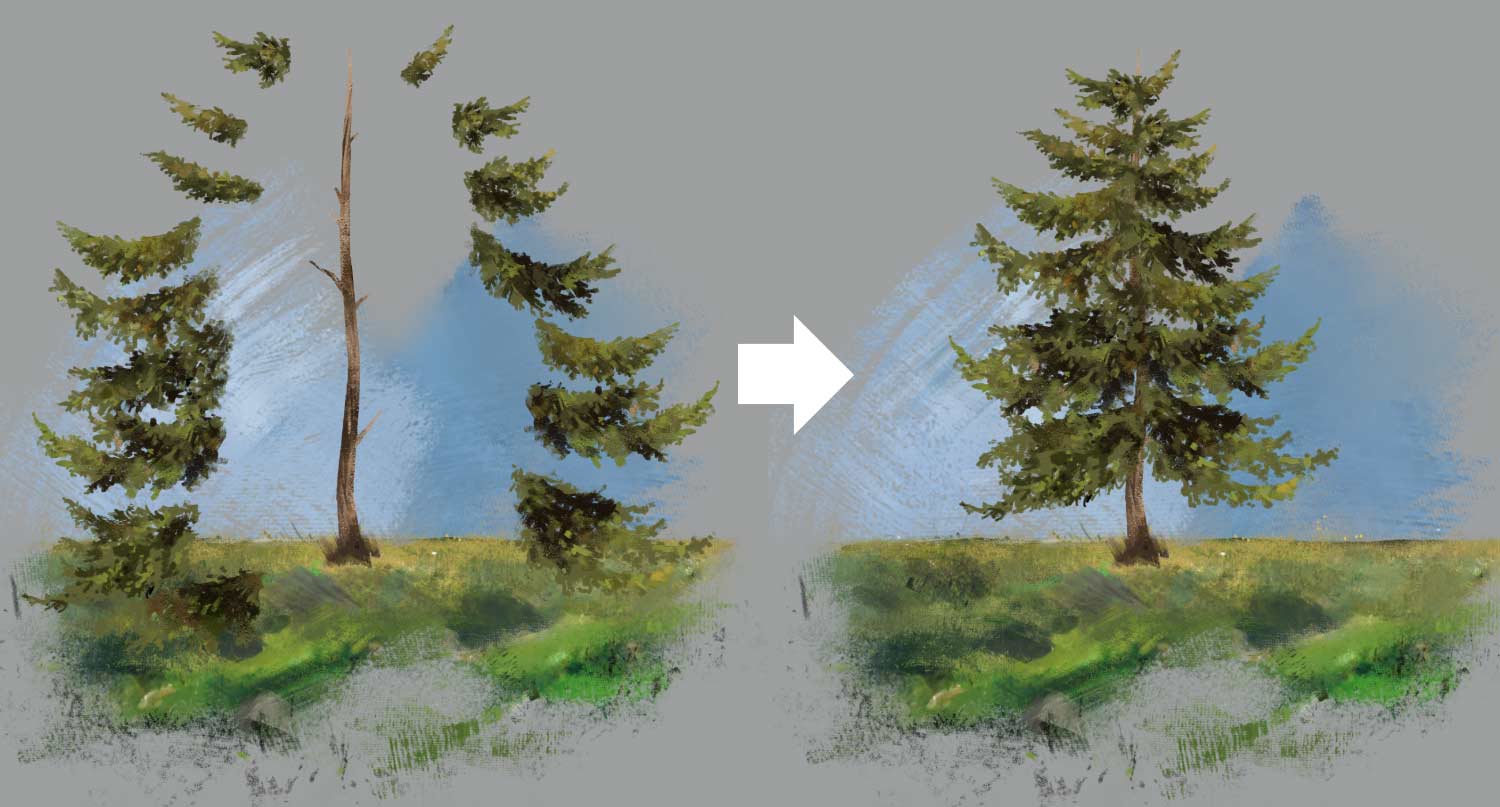

She's also started creating some tree kit parts that can be combined in different combinations and then animated so that they can sway in the wind:

Meanwhile, Tom has been working on a delightful stone-skimming mechanic. We're experimenting with several activities that feel thematically relevant for the world, and may at first appear to be satisfying but inconsequential toys. However, they will turn out to have genuine impacts will be relevant to the narrative or to the wider gameplay arc.

He has also been working on some level design experiments, and we've been thinking deeply about the platforming aspects of the game. This game isn't like Celeste - it's not intended to create fun out of immense hand-eye coordination challenges. But the risk is, if there's no challenge, then the game could end up feeling a bit hollow and lifeless - without risk, there is no reward. Let us know if there's a game that you think we should try that gets a really good balance here!

Of course, there's a lot more to the game than just platforming - so we don't have to rely on this on its own to keep the player's interest. The other primary ingredients in the mix are the narrative and the strategic planning, a bit like in 80 Days.

And finally, after our call for animators last week we've had lots of fantastic submissions, it's been a pleasure to look through so many beautiful portfolios. We can't wait to see our character come to life in game!

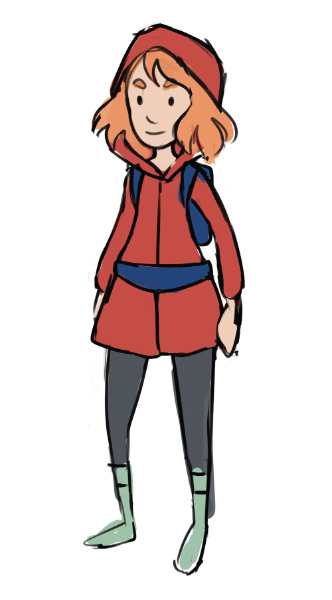

Calling hand-drawn animators!

—

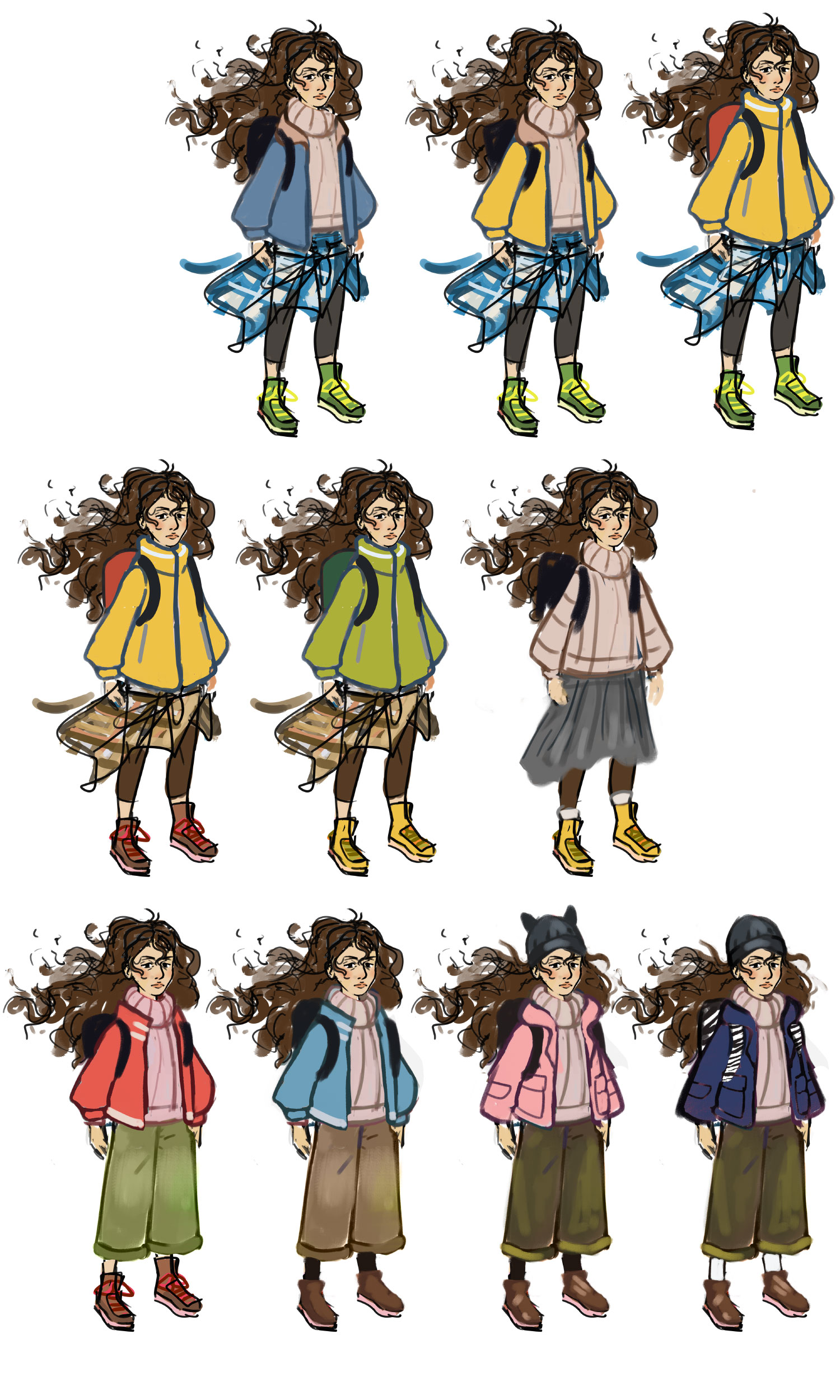

At the end of last year we experimented with using Spine to animate our main protagonist. Our animator friend and colleague Martin (who's been working on his own incredibly-named Schrodinger's Cat Burglar) gave us a helping hand, and started producing idle and run cycle animations to help us prototype the concept with our latest character design.

But as we experimented with Spine and 2d rigged animation, we increasingly realised it was perhaps the wrong direction to be pushing in. Although 2d rigged animation can give you very smooth results, it's also quite limited - for example you can't easily turn your sideways-facing character to look forwards at the camera. The advantages are that once you have a rigged character, it's relatively straightforward to create animations since it's equivalent to manipulating a shadow puppet.

By comparison, hand-drawn animation requires you to... well, hand-draw every single animation from scratch. But in return, the results can look incredible - have a play of Spiritfarer (character art below) if you don't believe me! Hand-drawn animation can add a huge amount of charm and character.

They also seem like the perfect fit for our environment art, which has a painterly aeshetic - we think they will sit together wonderfully.

We have one big problem though - we don't know any traditional hand drawn animators! Annie is our in-house artist and illustrator, and produces beautiful work, but we could do with some help producing pencil test frames that she could do the finishing work on.

Work with us!

UPDATE: We have now found our animator, thanks to everyone who applied!

So, here's the plan: if you're a freelancer and you think you'd like to work on our highland game (or know someone who'd be a good fit), please get in contact. Here's how we'd like to run it:

- We strongly encourage women, BAME and other minority background candidates to apply.

- A timezone closer to the UK is preferable. The work will always be remote.

- Send an email to [email protected] with "Highland Animation" in the subject line, and a link to a portfolio or sample animation work.

- If you seem like a good fit for the project, we'll ask you for a fully paid art test (we're likely to ask for a few of these from different people, assuming we get enough responses).

- We make a beautiful game together.

Happy New Year everyone; may this one be better than the last!

Research!

—Research!

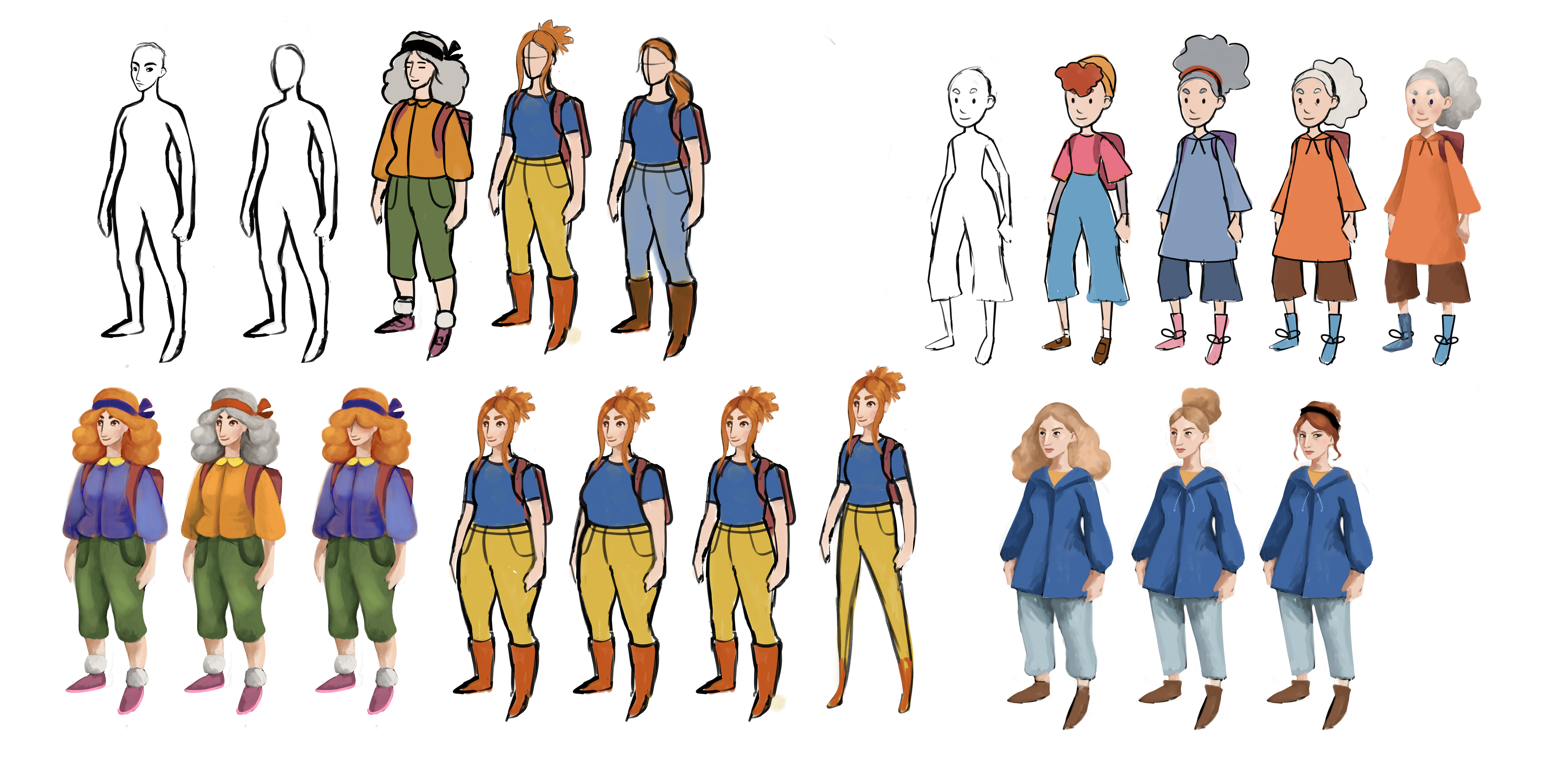

Character Concepting - Part 2

—[ TV ANNOUNCER VOICE: Previously on Character Concepting! ]

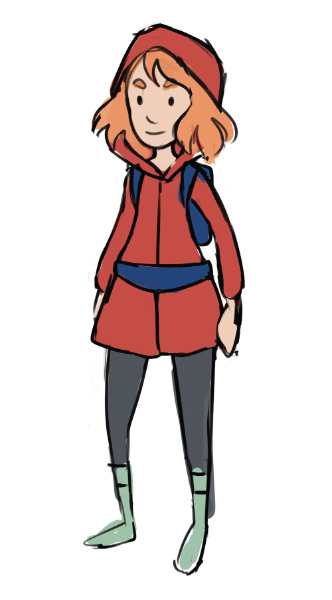

For year we'd been really happy with our character design sketch:

But when our art director Paul came on board, we started to revisit the character design so that she would fit better into the overall art direction. This design was a bit overly cartoonish and didn't fit with the more realistic background art so well.

She was also not entirely fitting with the narrative that Jon was starting to weave. We decided we needed a character who was a bit more grounded. She exists in a world that can be beautiful but also unforgiving; she has a difficult journey to make.

We loved this new direction. And so we started to narrow down the design:

But those were a bit too young. We felt like our protagonist was more like a 14-15 year old.

A pair of socks and some hair experimentation later, and we were all really happy with the design. We've also being going back and forth on whether the art should have (possibly sketchy) outlines, or be clean.

Here's a version with thin outlines. What do you think?

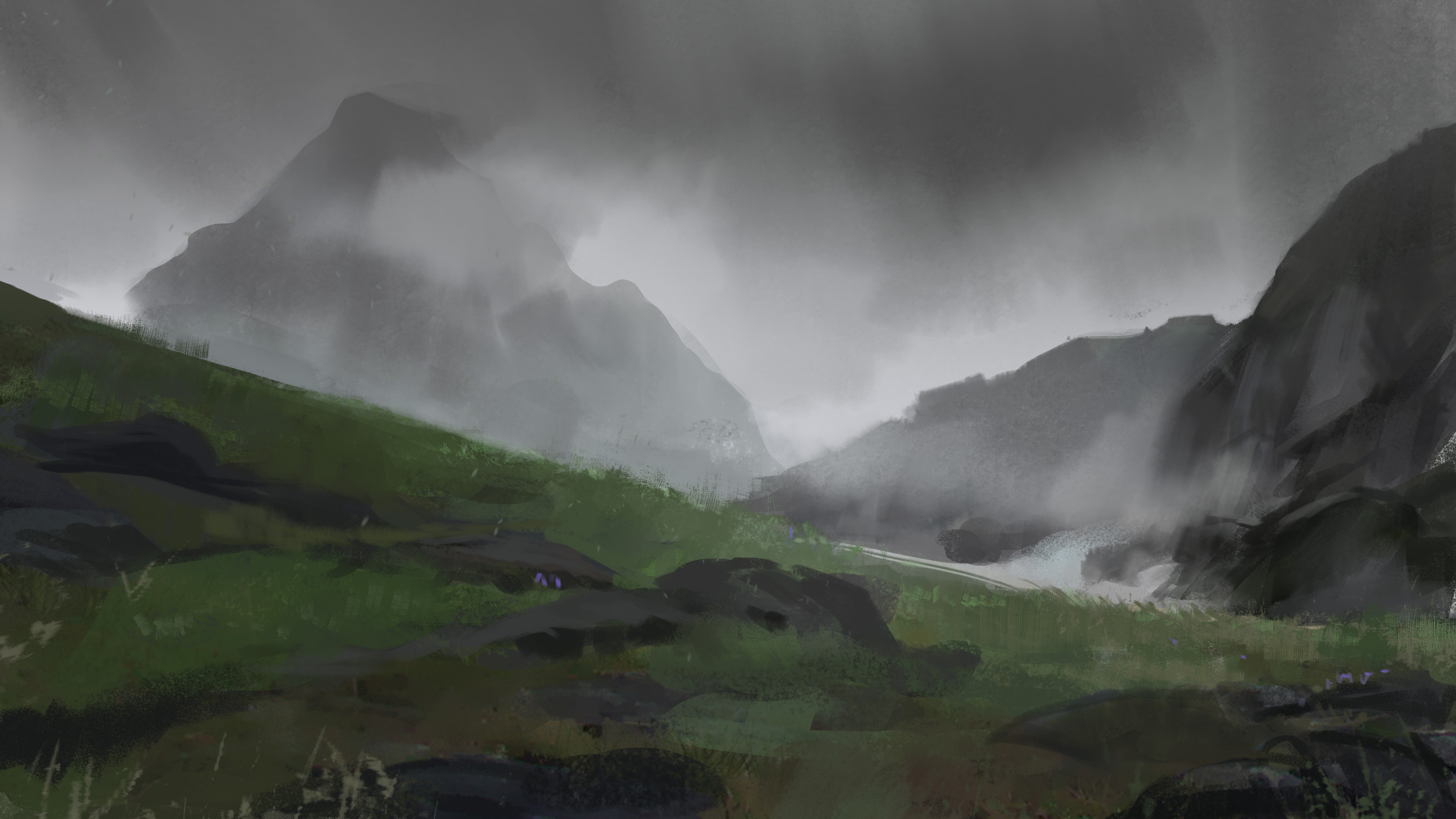

The art of the highlands

—

It's really important to us that our game strongly conveys the unique feeling of the highlands. There's a strong distinction that you feel being in the Scottish mountains compared to say, the European alps or Yosemite National Park. Scottish mountains aren't the highest, the jagged-est or the pointiest. But they have a darkness and weight to them that's only really shared with places like Iceland or perhaps parts of Scandinavia. They can be very lonely too - the further North you go, the further from civilisation you'll find yourself.

Our players don't all need to be fans of the Scottish highlands of course, even if we are! The point is to create a unique and strong aesthetic that's not just "generic green hills and rocks".

Part of capturing that aesthetic has been about finding an art style that can reflect it with authenticity. We wouldn't want to go with anything too bright or cartoony, so we think a level of stylised realism could do the trick.

The reason we approached Paul first about helping us out with art direction was that his work is both painterly yet has a sense of effortless realism; he's one of those concept artists who can convey a lot with a few important brush strokes.

We think his concept art above is a fantastic example of this! He's also produced an animated version of it that demonstrates parallax, and we'll share that in a future update.

When Paul first joined the team, he started off with a few loose studies to get a sense of the environment: the different times of day, weather and the textures in the foreground. These are a bit looser than our final intended art style, but the looseness is a good demonstration of how much can be achieved with so little!

Finding an art director

—In all of our past games the art direction has been primarily my (Joe’s) responsibility. I’m a bit of a jack-of-all-trades-master-of-none, and although I love art and I have artistic opinions, I’ve often been stretched a bit thin, especially on Heaven’s Vault.

One thing we decided very early on is that our highland game has to be absolutely gorgeous, so on this project, it was time to find some outside help - someone who could help us define a beautiful, consistent look for the game.

We were keen on a painterly aesthetic, to give the sense that you’re playing inside a rich, lush landscape painting.

Our first choice was Paul Scott Canavan. He’s an exceptionally talented illustrator and art director. Oh, and he's Scottish.

Just take a look at some of the gorgeous work from his website:

So, we dropped him an email. Just a few minutes later, and we had an enthusiastic yes! He loved the concept and was really eager to work with us to make it a reality.

Paul isn't just a brilliant illustrator; he's been doing a great job of deconstructing the game's art style, breaking it down so that we can work together to build it back up in-game out of the fundamental pieces.

By the way, the key art at the top of this page is his - and it’s the overall look we’re aiming for on this project. We can't wait to show more of what we've been working on together!

Character Concepting - Part 1

—We started designing the look of our protagonist back in the summer of 2019, while working on Pendragon.

Here are some of Annie's lovely early sketches:

For a long time, we had settled with the following design. In fact, we've had her in-game for a while, with some early prototype animations:

We've been doing some new work on the character design since then. Watch this space for Part 2!

Update: Part 2 is now here

The story so far

—Welcome to this brand new little update blog for our as yet untitled game that's set in the Scottish Highlands. (Okay, we have a proper name for it, we're just not ready to say what it is yet!)

First, let's get up to speed. What kind of game is it that we're making?

In some ways it's very similar to our previous games - it's about travel, it's replayable, and has a strong branching narrative.

In other ways, it's very different. This game has a side-on perspective and has 2d platforming elements, which is very much uncharted territory for us!

Something else that's very different: we're planning to be more open with the development process than we ever have in the past. We're going to try and post regular updates. So please hold us to account if we haven't posted in a while!

That's it for now! Watch this space for more...